On the Evolution of Law and the Lawyer

- Nitesh Daryanani

- Apr 10

- 7 min read

"There is a time when silence is betrayal." - Martin Luther King Jr., Beyond Vietnam, 1967

In the long shadow of the Trump presidency, a reckoning is underway—not in the courts, not yet—but in the court of public opinion, among students, clients, and even associates. The target isn't just the politicians and billionaires; it's the elite law firms that chose to say nothing. In the face of creeping authoritarianism, democratic decay, oligarchy and blatant illegality, many of the country's most powerful legal institutions have offered nothing but silence.

Now, that silence is cracking. Law students are organizing boycotts. Clients are quietly parting ways. And beneath the surface, a deeper unease is taking shape—a quiet uncertainty about whether this wave of frustration will lead to anything more than churn. What is the lawyer for? The question lingers, not just as critique, but as invitation—and it is this invitation that animates what follows.

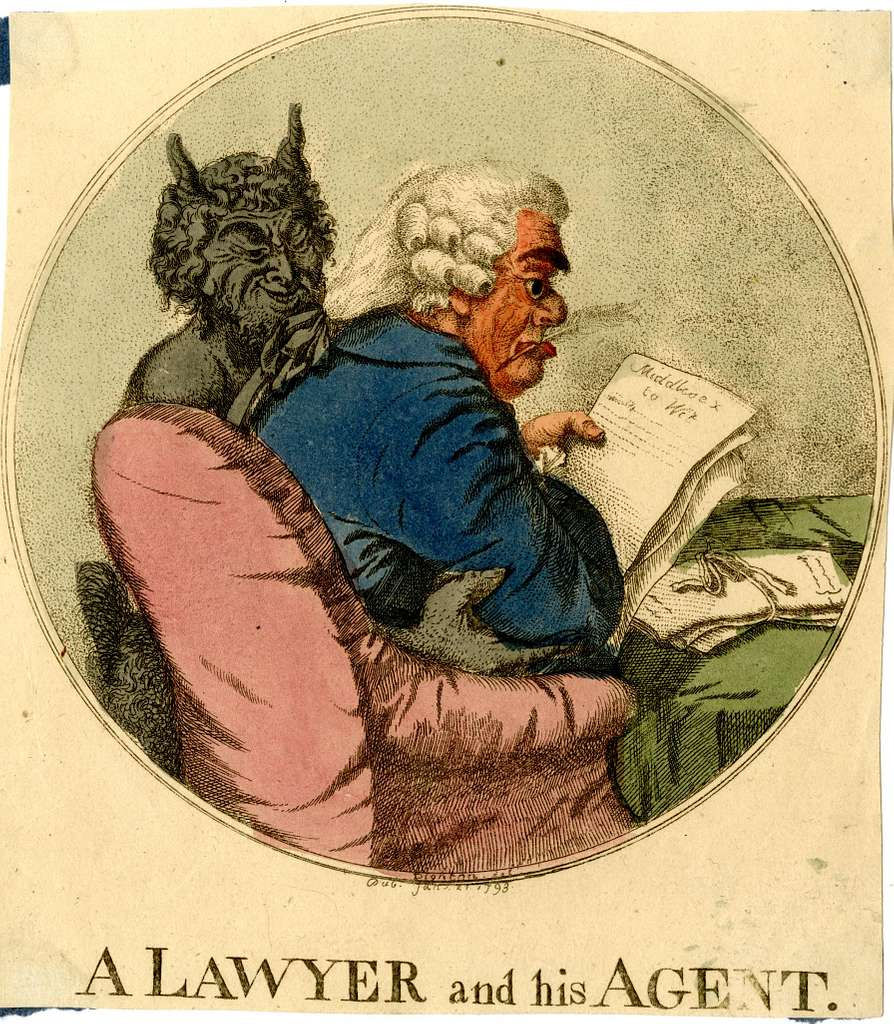

Is the lawyer merely an agent, bound by duty to the client regardless of consequence? A technician of argument? A neutral instrument in a system that pretends to be above politics?

Or is the lawyer's role something else—a participant in a living law, responsive to the shape of society, answerable not only to precedent but to justice itself?

This is not the first time the legal profession has faced a moral crisis. But perhaps it can be the last time it meets one with nothing but procedure and posture.

At regarder, we believe the law is not a fixed edifice but a practice that must be reshaped—through thought, through attention, through action. This essay begins that reshaping. It is not a condemnation, though there is much to condemn. It is a beginning.

I. The Backlash

The current disillusionment with the legal profession didn't arrive overnight. It settled in gradually—accumulating in moments of silence, in the space between what the law promised and what it delivered. For many lawyers and law students, the past several years have eroded the faith that law is, at its core, a force for justice. In its place, a different picture has emerged: a profession too often organized around risk aversion, reputational management, and the appearance of neutrality above all else.

The silence of powerful firms in moments of democratic crisis has not gone unnoticed. Neither has the pattern of selective outrage, procedural hedging, or behind-the-scenes accommodation. What once looked like professionalism now feels like complicity.

There is a growing sense—felt most acutely by the youngest members of the profession—that law, as currently practiced, is not meeting the moment. That it is too slow, too insulated, too aligned with the preservation of power to offer a credible response to the challenges we face.

From the revolving door between Big Law, government agencies, and corporate boardrooms, to the shaping of public policy by private counsel, the legal profession has long been entangled with power. In past decades, former regulators have returned to white-shoe firms to help their clients navigate (or neutralize) the very rules they once enforced. The system has been designed not only to interpret the law, but to bend it in service of entrenched interests. With that realization comes a deeper question: What, exactly, is the lawyer's role in this world we're inheriting?

II. From Moral Agent to Technician: The Narrowing of Legal Practice

The figure of the lawyer has always been suspended between two poles: the citizen and the servant, the moral agent and the hired hand. But the history of this tension reveals a troubling shift—from law as a pursuit of justice woven into the shared fabric of political life to a profession increasingly defined by technical expertise rather than moral clarity.

In ancient Greece, justice—dike—wasn't merely about laws but about balance in society. Advocates were citizens deeply involved in civic life, helping to define what was good for the community. For Cicero in Rome, natural law meant appealing not just to written statutes but to a deeper, shared sense of right and wrong. Through the Enlightenment, thinkers like Kant saw law as an aspirational project aligning human conduct with what reason revealed to be just.

Within this historical framework, lawyers were both advocates and architects, debating not just individual rights but the very contours of the common good. They participated in a tradition that viewed law as a moral enterprise—one concerned with human flourishing, not merely procedural correctness.

But over time, this aspirational conception faded. With the rise of the modern state and market capitalism, law became increasingly synonymous with order. The lawyer, once a public thinker engaged in moral reasoning, transformed into a technician of rules—navigating a labyrinth whose logic is increasingly opaque even to its designers.

Today's legal system often resembles Kafka's chilling vision: a world where justice is not absent but drowned in process. Courts retreat into rigid categories and doctrinal comfort zones rather than confronting the complexity of the world they're tasked with adjudicating. As society changes and legal issues grow more interconnected, this resistance to intellectual risk has become a bottleneck. Systems grind against one another, litigation becomes costlier and slower, and growth—legal, social, economic—is stifled.

Perhaps most troubling is the profession's embrace of neutrality as its central virtue—a polished shield against moral responsibility. In the name of neutrality, lawyers advise authoritarian governments, defend corporate polluters, launder reputations, and underwrite repression—all while insisting they are simply doing their jobs. But neutrality is not the absence of politics. It is the tacit endorsement of the existing balance of power, the refusal to act dressed up as professionalism.

This neutrality begins to fray the moment the stakes become personal. When the law threatens your vote, your body, your child, the illusion collapses. Neutrality is a comfort reserved for those whose lives are not on the line. For everyone else, the law is already political—already a site of struggle.

There are lawyers who understand this. Public interest lawyers, public defenders, immigration advocates, human rights attorneys—they do not pretend to be neutral. They know that law is not an abstract system but a terrain of conflict, and they enter that terrain with intention. Their work exposes the ruse at the heart of elite lawyering: that one can be involved in power without ever taking a side.

This is why the backlash against Big Law is so charged—not just because of what these firms failed to do, but because of what they continue to pretend they are not doing. The claim of neutrality is not just cowardice. It is, increasingly, a lie.

III. Law as Living Practice

What if law were not a fixed architecture of rules, but a living language? What if it was less a system to administer than a field to cultivate—a medium through which we negotiate our shared lives, revise our understandings, and remake the world?

This is not a utopian question. It is a return to an older truth: that law is a living practice, shaped not by precedent alone but by public life, moral struggle, and the crises of its time. The difference now is that we are beginning to admit it. The veneer of objectivity is cracking, revealing something more dynamic—and more dangerous: the truth that law is made. And if it is made, it can be made otherwise.

This is not how most lawyers are trained to think. In elite law schools and corporate firms, law is taught as a closed system: memorize the rules, analyze the precedent, argue the case, and don't ask too many questions about what lies beneath.

But younger lawyers are beginning to reject that script. They are refusing to separate legal reasoning from moral reasoning. They are demanding that law be accountable not only to clients, but to communities—to history, to harm, to hope.

To treat law as a living practice is to insist that interpretation is shaped by what we choose to notice, question, and engage with in the world around us. That legal work is not simply technical, but ethical and political. That the law is not merely what courts say, but what people contest, demand, and remember. This means lawyers must not only analyze the world—they must take part in changing it.

That is what we are trying to do here, with regarder.

To regard is to look with care, to attend, to bear witness. It is the opposite of neutrality. It is the refusal to look away. And in a time when so much of the legal profession is organized around the art of looking away—away from consequence, away from complicity, away from the people the law so often fails—regarder is an invitation to look closer, and to act from what you see.

As part of this effort, we're building a legal knowledge platform—a tool designed not just to organize information, but to transform how we relate to it. This isn't another case database or AI legal assistant. It's a living infrastructure for dialogue, discovery, and shared understanding—one that invites lawyers, researchers, and the public to trace how law moves, mutates, and matters. More on that soon. For now, it's enough to say this: if law is a living practice, it needs living tools.

The law is already alive—though many pretend not to notice. It breathes in courtrooms and classrooms, in the whispered doubts of those who entered this profession to do good and now wonder if they're doing anything at all. Every legal interpretation is an act of world-making, shaped by what we choose to see, normalize, or resist. We need spaces where this power is wielded consciously, where participation is accountable and oriented toward justice.

That is what regarder hopes to be—a recognition that the legal profession, like the law itself, is fluid and full of potential. This potential awakens the moment we stop pretending to be neutral and ask instead: What kind of law do we want to live in? We invite you to help us build the answer.

What do you believe the lawyer’s role should be in society today? (Choose the one that resonates most with you.)

A neutral technician serving the client, no matter what

A moral agent balancing client service with public good

An architect of justice, actively reshaping the law

A bystander—law can’t fix what’s broken in society

Comentarios